Code reviews

And why they're probably the most important software engineering skill

If I could go back in time ten years and give myself career advice, I’d say this: “Get better at code reviews.”

This should go without saying. Code reviews are important. Lazy or ineffective code reviews are how you end up with a codebase that’s awful to work in. You drive the change you want to see by pushing folks to be better in the ways you care about.

Besides just getting people to react to the immediate feedback you provide, giving good code reviews starts to embed organizational knowledge about how things should be:

I’m often a broken record reminding my coworkers that they need to change their

z.string()toz.uuidv4()orz.string().nonempty().max(256)or whatever else is going to prevent us from a user adding the entire Shrek screenplay into the name of a folder in their account1.When you read and write data, you need to add appropriate locking.

A bunch of assertions as individual test cases can just be one test case, or an

it.each().Outgoing HTTP requests need timeouts and

User-Agentheaders.JavaScript doesn’t have 64-bit integers, don’t use

int8in the database unless you really really know what you’re doing.Don’t use a

^on the version numbers for important dependencies. Pin to exact versions.

The list goes on! Folks will start repeating good suggestions in their own code reviews, and eventually there’s enough good examples that folks will copypasta the good stuff and think the stuff you don’t love is smelly.

But that’s not the big reason why I’d tell myself to get good at code reviews.

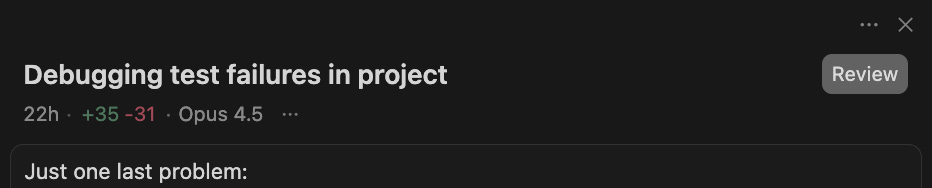

In a world of AI-augmented programming, programming is code review. Hell, Cursor even calls it “Review” now:

Being a “good programmer” when you’re using a tool like Cursor or Claude Code doesn’t mean:

Prompting well

Making the thing work

Running lots of agents at once

Getting really nice output

It means looking at what the model produced and offering real, critical feedback to get it to shape its code into what you want to see in the codebase. If you’re only prompting the LLM enough to get to a working solution, you’re not doing your job, and in the process you’re making it more and more difficult for you and the other humans on your team to work in the codebase.

And you should care!

Right now, we’re crossing a threshold where many folks in many orgs are using prompt-based augmented coding more often than not. Naïvely trusting the model is pretty easy:

It wrote tests, or you could trivially get it to write tests

The code looks robust

The code works

It looks like it was written defensively

You completed the task fast, and there’s more work to be done

But there’s a real risk: models today still don’t do a good job of considering the codebase, just the task at hand.

Let me offer some real examples.

Tests that don’t matter

I recently reviewed a coworker’s PR that was obviously written by AI. It added about 20 tests, clocking in around 3-4 times the actual feature code. Of those tests, maybe a dozen were unnecessary or outright useless:

Test cases that weren’t meaningfully different from other test cases

Test cases that could have just been simple assertions in a single test case (“passing undefined should return null”, “passing null should return null”, “passing an empty string should return null”)

Test cases that didn’t cover any new ground (“it should work”, “it should work with two items”, “it should work with three items”, “it should work with a real example”; “it should work with one space”, “it should work with no spaces”, “it should work with lots of extra whitespace”)

At best, these do nothing. At worst, they make your test suite slow, reduce the readability of the tests, and make it complicated to update existing code when requirements change.

Especially for the inexplicable test cases, a human might look at these and think “well there must be a reason they explicitly tested for three or more items” and suddenly we’ve accidentally erected Chesterton’s Fence. Nope, the AI was just having fun dumping tokens.

Tests should make sure your code works, but they should also go out of their way to document your code to show what you as the programmer care about. A well-written test suite shows future engineers where your head was at and helps to show how things behave at the edges. AI-written test cases do not do that. They’re there to prove the code works for some definition of “prove” and “works”.

The fix: you should be reading the tests and deciding if they even make sense. You would expect a good code reviewer to call you out on bad test cases, and you should expect to call your AI out on bad test cases in the same way.

A little bit at a time

A new feature was released at work, and the code powering it has become large. The feature is large, and necessarily complex—it allows users to do complex, multi-step actions.

But the code is far more difficult to work with than it should be. Much of it was written by AI. And it’s easy to tell: there’s many chains of functions that really could use a good refactoring. Here’s one such chain of functions that could use a good once over2:

invokeProjectExecution

executeProject

executeProjectTasks

createJobsForTasks

createJobs

createJob

There’s something to be said for making the code modular in small, testable chunks. That’s not what’s happening here. This is a pattern I’ve seen come up again and again with AI-generated code: the model works additively. It doesn’t look at the whole of what is running and say “this has a smell, we should refactor.” Its task isn’t to refactor, it’s to accomplish what its prompt was.

Ultimately, just looking at the diff of the code isn’t enough. You need to contemplate the stuff upstream and downstream from your code, because there’s a good chance the bits your model changed don’t feel great in context.

The fix: you have to look at the output of your model in the context that they’re used and decide whether the job is really done. Yeah, it might work, but if you’re just bolting stuff on again and again, eventually you end up with a spaghetti mess where nothing is in a predictable spot, and control flow snakes its way through your codebase.

Repeat yourself

It’s a little bit ironic that one of the most common pieces of advice in software engineering is “don’t repeat yourself.” And even more ironic that the best frontier coding models can’t really seem to get the message.

Before writing this post, I literally finished up reviewing a coworker’s PR (written entirely by Claude) that took some code that used one vendor and wrote a second version of it that accomplished ~the same task with a different vendor.

The original code had a snippet in a large function to clean up the original vendor’s output, using some regular expressions to strip whitespace and normalize formatting. And that cleanup code was duplicated into the new code for the second vendor. Anyone writing this code manually would have taken the opportunity to refactor that logic out into a helper function. It could probably even use some tests!

Claude happily left a copy of the code, though, because again: AI isn’t trained to maintain a healthy, DRY codebase, it’s trained to get its job done really well. The job, in this case, was creating the second implementation for the new vendor.

The fix: pay attention! Spend the extra few minutes looking at a PR. One duplicated snippet isn’t the end of the world. But let it slide 50 times, now your codebase is starting to look pretty sloppy. If your coworkers each let it slide 50 times, now your codebase is jam packed with many hundreds of duplicated snippets.

A preventative tip

Every time you leave a comment on a code review, consider writing a line to your CLAUDE.md file (or AGENTS.md or whatever you use). I like to add a docs/ directory to my repos and reference it from cursor rules. The more you document norms, the better the tools will be about following those norms—though it’s not an exact science.

I largely agree with the advice in this recent post: https://www.humanlayer.dev/blog/writing-a-good-claude-md

A quick shoutout

Quick disclosure: I’m NOT being compensated to write this.

There’s a bit of irony to use AI to fix some of the insufficiencies of AI. I’ve been using Tanagram for a few months now, and it’s been a really awesome tool for code reviews. Imagine a linter, but instead of having to write complicated rules that walk an AST tree and probably don’t match all the things you care about, it uses an LLM to flag problems.

You can write “fuzzy” rules that describe the kinds of problems you want to identify, along with descriptions of why it’s important and what to match. Tanagram then leaves comments on Github PRs with links back to the rules. It’ll even read your PR comments and suggest new rules based on them, and give you tools to backtest rules against your old PRs.

Tanagram doesn’t make reviews easier, but it does save you from having to be a broken record. And hopefully soon, it’ll integrate tightly with AI-powered editors to avoid issues getting to the review phase in the first place.

Two thumbs up for Tanagram from me. 👍👍

Yes, I had to explain to a PM why we “couldn’t just build an index on folder names” and this was one of the reasons.

The names have been changed to protect the accused

Also considering writing lint rules for some of these. With LLMs it's become the easiest it's ever been to write custom lint rules.

100% agree with this. Engineering has always been a skill of communication, and the now more than ever the emphasis needs to be on planning, reviewing, and testing... three skills that many engineers I know (myself included) have traditionally avoided!

I wrote a similar treatise recently, you may appreciate it, Matt - https://mikebifulco.com/newsletter/next-great-engineering-skill-is-context-not-code